The Sacred Feminine in LDS Art & Theology

Center Gallery, NYC | January 14- March 6, 2022

"The doctrine of a Heavenly Mother is a cherished and distinctive belief among Latter-day Saints,” notes The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' official gospel topics essay “A Mother in Heaven.” LDS theology diverges from broader Christianity with its belief in a Heavenly Mother, who “stands side by side with the divine Father.” Church leaders proclaimed in 1995, “All human beings—male and female-are created in the image of God. Each is a beloved spirit son or daughter of heavenly parents, and as such, each has a divine nature and destiny."

Although the doctrine of Heavenly Mother has been a part of LDS theology since the early Church, the precise status of her divinity and how that ought to affect spiritual practices is ambiguous. Artists, particularly poets, have always played an important role in exploring this issue. Relief Society General President Eliza R. Snow helped make the concept of Heavenly Mother widely known and accepted through her poem “My Father in Heaven” which became part of the LDS hymnbook as "O My Father” in 1877. It reads in part:

In the heav'ns are parents single? No, the thought makes reason stare! Truth is reason; truth eternal Tells me I've a mother there.

In the last decade, LDS artists have begun exploring ideas about Heavenly Mother's power and meaning in greater quantity and diversity than ever before, although the earliest known depictions date from the nineteenth century. Some artists have chosen to depict their figurative version of Heavenly Mother, while others have used abstract images to assert her unknowability as a divine being. Yet others have used figures or symbols to share the qualities they believe Heavenly Mother possesses. This exhibit seeks to examine the diverse ways that LDS artists engage with the concept of a feminine presence to which our spirits yearn, yet which is simultaneously more vast and unfathomable than the mortal experience can comprehend.

The Sacred Feminine in LDS Art & Theology is organized by Margaret Olsen Hemming. It was made possible by the generous support of donors to the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. Graphic design for the exhibition is by Cameron King.

John Hafen (American, born Switzerland, 1856-1910)

I’ve a Mother There (1908)

Gouache, 18 x 11 inches

Collection of Brigham Young University Museum of Art

In 1890, John Hafen was called a missionary to study art in France, where he learned from the masters of the time the use of color, how to apply light, and the broken brushstrokes of impressionism, all of which can be seen in his later work. When he returned, he used his new skills on the Salt Lake temple and then struggled to make a living as an artist.

The LDS Mission Presidents Ben E. Rich and German E. Ellsworth, impressed with Hafen’s work, suggested he turn Eliza R. Snow’s poem “O My Father” into a series of illustrations that could be made into a booklet and sold. The two men offered to finance the project, keeping only a small amount of the proceeds and returning the rest to Hafen. Rich, Ellsworth, and Hafen saw the booklets as a missionary opportunity, as the images could speak to people about the nature of God in a new and different way. Hafen wrote at the time, “I am impressed with the means that pictorial art might be of spreading the grand truths which are in that poem.”

Rich and Ellsworth tried to convince the First Presidency of the Church to purchase the booklets and distribute them to missionaries, but to no avail. Although Church President Joseph F. Smith offered to buy the first copy printed, the Church ultimately decided not to get into the business of publication, much to Hafen’s disappointment.

Hafen used his wife, Thora, and his daughter, Delia, as models for the mother and child depicted. The figures stand in a close embrace against a clear sky, an example of enduring parental love. Although the subjects are mortal, Hafen wanted viewers to see the image as a template for Heavenly Mother and her children and contemplate their relationship with her.

Lisa DeLong (British-American, born 1974)

The Key of Knowledge (2019)

Pigments and leafing on paper, 36 x 24 inches

Collection of the artist

Lisa DeLong’s art probes the geometry of the sacred, tapping into an ancient tradition of melding mathematics with religious art. As DeLong writes, she finds beauty “in chaos and cosmos.” As she considered a work of art exploring the sacred feminine, DeLong felt her geometric artistic style was particularly well-suited to the task, as symbols allow more freedom to think about who or what God is. Rather than thinking about a specific figure, she invites the viewer to consider “What is Heavenly Motherliness? What are her qualities and what is my relationship to her?” The title of DeLong’s work references LDS Relief Society President Eliza R. Snow’s poem “O My Father,” which helped lay out a theology of a mother in heaven:

I had learned to call thee Father through thy Spirit from on high

But until the key of knowledge was restored, I knew not why.

In the heavens are parents single? No, the thought makes reason stare!

Truth is reason, truth eternal Tells me I've a mother there.

The nineteen interlocking circles in the central figure of this piece symbolize ultimate perfection as the sum of seven and twelve, two numbers used in scripture to represent wholeness. While on a macro level the shapes are circles, the circles are made of tiny squares, illustrating the connection our heavenly parents hold between heaven and earth, the spiritual and material worlds. As children of God, we can use our earthly experiences to find heaven. The circles made from squares originally derived from a quilting design, a nod to the early LDS women who taught and wrote about their Heavenly Mother while sewing and quilting together.

The smaller shape below symbolizes each individual person striving to echo the characteristics of their divine parents. The shapes rest on marbled paper, chosen to represent the organized matter of heaven and earth, created by God for the children of God.

Kwani Povi Winder (Santa Clara Puebloan, born 1989)

Welcome Home (2019)

Oil and metal leaf on linen panel, 16 x 14 inches

Private collection

Kwani Povi Winder’s mother is Santa Clara Puebloan and her indigenous family creates pottery in southeastern Idaho. Winder wanted her version of Heavenly Mother to honor that background. The shapes used in the halos deliberately tied together symbolism in Pueblo culture and in LDS temples. The “step down” shape means “home” or “our people” and the circle indicates perfection and continuation. The journey symbol in the shape of a swirl represents each individual’s unique life path.

Although Winder’s biggest hesitation in approaching the project was the question of how to portray perfection, she ultimately embraced the process by using her mother as a model. Winder’s LDS childhood was interwoven with the stories of indigenous culture, making the concept of a mother earth or a divine creative presence very familiar to her. In this way, the artist’s experiences with the doctrine of Heavenly Mother are tightly tied to her relationship with her mother.

Susana Isabel Silva (Argentinian, born 1976)

The Earth Rolls Upon Her Wings, 2021

Italian fabriano paper, 39 x 31.5 inches

Collection of the artist

“The earth rolls upon her wings, and the sun giveth his light by day, and the moon giveth her light by night, and the stars also give their light, as they roll upon their wings in their glory, in the midst of the power of God. Unto what shall I liken these kingdoms, that ye may understand?”

- Doctrine and Covenants 88:45-46

As a kind of map of the universe, Doctrine and Covenants 88 had enormous influence on the early LDS Church, prompting the building of the Kirtland temple and a more serious academic study of scripture and gospel topics. This artwork’s title and its reference to the enigmatic verse 45 from this section suggests that with an ongoing restoration, a better understanding of the roles Heavenly Mother plays in the temple and in the heavens will follow.

This artwork represents a synthesis of the formation of the world, portrayed in a delicate knitted paper and displaying Heavenly Mother’s role as an eternal co-creator. Her influence— harmonious, exquisite, and sensitive—illuminates every corner of the universe. We can see it in the bright light of the heavenly bodies above or in the reflection of God’s face in the goodness of kind people.

The geometry of Silva’s work holds similarities with Lisa DeLong’s piece The Key of Knowledge, elsewhere in this exhibition, which also explores questions of sacred repetitive patterns. The shapes created as planets orbit the stars, the lines of bifurcated angles and circles—for the artists, these cosmic designs point to God.

Melissa Tshikamba (Canadian-American, born 1994)

Honey (2019)

Oil on wood panel with gold leaf, 12 x 16 inches

Private collection

While Honey may not immediately conjure ideas of the sacred feminine, those familiar with Latter-day Saint history, theology, and symbolism may appreciate Tshikamba’s rich references throughout this piece.

Bees and honey are frequently used as references to womenin art, as the queen bee plays an essential role in every hive. But bees and beehives also played a significant symbolic function in early LDS Church history, with the unity, industry, and cooperation of the beehive serving as an example for Church members. Beehives appeared on Church literature, sacred buildings, and government documents. Bees and beehives continue to this day to have emotional importance to many members of the Church as a symbol of the effort to build Zion.

The circle or halo of gold represents God, illumination, enlightenment, joy, and royalty. Tshikamba has indicated that the hands represent each of us in our mortal journey, striving to touch the divine. Rather than being completely separated, the golden celestial glory drips down onto the hands, giving the temporal being a divine encounter. These drips echo the beehive shapes, reminding us that building Zion may be the best way for humans to find God. The upward motion of the bees and hands symbolize progression, the hope that we can each find our way back to our heavenly parents. As Tshikamba writes, “I believe we are all gods and goddesses having a human experience.”

Richard Lasisi Olagunju (Nigerian, born 1974)

Goodly Parents (2019)

Coral beads on wood, 40 x 28 inches

Collection of the artist

“I, Nephi, having been born of goodly parents . . .”

- 1 Nephi 1:1

The first words of the Book of Mormon situate the primary narrator, Nephi, in the social context of his family. This legacy will have rippling consequences throughout the rest of the book. Olagunju’s beaded artwork is intended as a belief in the divine role of parents and the global need for kind and consistent family.

The intricate beadwork includes a border of patterns found in Yoruba textiles. Both figures wear a dashiki, a colorful garment with embroidered collars found across Africa and the African diaspora. The twelve braids of hair represent the twelve tribes of Israel, an unusual and forceful symbol for a female figure. By interweaving Book of Mormon references and West African cultural symbols, Olagunju makes a beautiful statement about what is intrinsically divine.

Laura Erekson (American, born 1983)

Holding Her Halo (2019)

Rust, felt, petals, and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 60 inches

Collection of the artist

Created while the artist was pregnant with her third child and had two toddlers in her art studio, Holding Her Halo is the product of Erekson’s awakening to her desire to have a relationship with her mother in heaven. Having children prompted her to ponder her mortal identity as well as her eternal one and seek to better understand where she came from and what she had the possibility to become. This figure represents Heavenly Mother as well as the divine potential of all women. She holds her own halo in place; it does not merely float behind her. Her love, power, and strength keep it secure.

Erekson’s piece highlights the materiality of the LDS concept of the divine. Latter-day Saints believe God has a body and that bodies are sacred gifts of God. Erekson’s use of a variety of household items intersects the spiritual and the physical, deleting the difference between the divine and the mundane. The halo is made of the impressions of screws, safety pins, hammers, keys, a ring, pieces of a tap and die set, sunflowers, and needle-nosed pliers. These items demonstrate an array of skills and aesthetics and also take on specific meanings such as inclusion, priesthood, time, and eternal happiness. The palm leaves hanging from her arms as wings symbolize victory, triumph, peace, and eternal life. Part of the lace-like texture on the figure was created with crayons and a baby’s pacifier, demonstrating the sacredness of creation and childhood as well the comfort a holy mother offers her children. This version of Heavenly Mother is not only about the divine figure, but about the process of becoming sacred.

Amber Lee Weiss (American, born 1991)

Romana (2019)

Hand-cut magazine and photograph images on fabric, 23 x 11 inches

Collection of the artist

Two years ago, Amber Lee Weiss suffered a miscarriage after strongly believing she would give birth to a healthy full-term baby girl. The experience propelled her into a faith journey in which she felt the need to reestablish her relationship with God in a new way. This included turning photographs of her maternal ancestors into artistic collages of angels. She felt that this experience of converting her maternal ancestors into something simultaneously divine and human, grounded in history and yet out of time, felt healing. Connecting to her family history helped her grieving process. As time went on, she also began making collages of images of Christ and using that to explore her testimony of God: who God is and what God means for her.

The title of the piece comes from the name of the artist’s great-grandmother, Romana Rodriguez, who presided over her extended family as the unquestioned matriarch. Honored by the entire family, she would sit in a large fancy chair with artificial flowers every year for her birthday as the family gathered to celebrate. Everyone acknowledged her as the embodiment of power, grace, elegance, and love, which is why the artist chose her as the face of her Heavenly Mother figure. Romana Rodriguez was not only a leader in her family, she also was the unofficial adoptive mother to many children in the community who needed a parent to care for them. When she passed away, the family gatherings came to an end. The family had lost the figure who had connected and unified them. As Weiss explains, “When I think of Heavenly Mother, to give her a face that makes sense to me, I think of my great-grandma Romana, of being this figure who brings people together.”

Annie Poon (American, born 1977)

The Scent of Stardust (2021)

Acrylic on canvas, 24 x 18 inches

Collection of the artist

Annie Poon originally created a piece similar to this one to illustrate an essay by Madeline Thatcher entitled “In the Garden,” a fictional narrative imagining Eve speaking with Heavenly Mother as she wrestled with whether to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The line “Eve’s eyes closed, breathing in the scent of stardust that lingered on her mama’s skin, remembering for a moment how she herself used to smell like that,” inspired Poon to create a figure that represents Eve and her mother in heaven simultaneously. For this exhibit, Poon reworked the figure with a different medium but similar concept. Like a playing card with a different figure depicted from the top or bottom, this piece is Heavenly Mother from above and Eve from below.

The stars in the woman’s hair indicate her place among the heavens. The artist’s own experience of living through a period of losing her hair made hair a personal symbol of strength and capability. The woman’s feet on the ground show Eve’s place on earth but also the artist’s belief in a sacred feminine who is warm and present in mortality. Rather than blaming Eve for the Fall from the Garden of Eden, Poon uses this piece to celebrate the important moment of all of humankind gaining more knowledge and continuing eternal progression.

M. Alice Abrams (American, born 1995)

We’ll Bring the World His Truth (2021)

Linoleum block print on handmade paper, 17.5 x 17 inches

Collection of the artist

Taken from the title of a well-known LDS children’s hymn, We’ll Bring the World His Truth is evocative of the early Church’s call to establish Zion throughout the world. Even as they traveled westward to colonize a piece of desert in what would become the state of Utah, the LDS pioneers imagined the restored gospel going forth to all the earth. This piece conceptualizes a global society of Saints with an expansive version of God that emphasizes the human ties we build on earth.

Joseph Smith taught that “all truth may be circumscribed into one great whole,” by which he meant that all truth ultimately comes from God and can be readily embraced. For Abrams, each individual depicted in this artwork was inspired by their heavenly parents to deliver their bit of truth to the earth. The temporal knowledge and gifts they share mingle with the spiritual knowledge which comes from God. These people have halos, not to deify them, but to nod to the work they did to contribute to truth while they were on earth. The heavenly parents and Jesus Christ have detailed halos to distinguish them.

Some of the people featured (from top going clockwise):

Heavenly Father, Heavenly Mother, Nephi, Mother Teresa, Martin Luther King Jr, the Dalai Lama, Jesus Christ, Malala Yousafzai, Gandhi, the Pope, Joseph Smith (and Smith’s faithful dog Old Major), Emma Smith, Joan of Arc, Adam and Eve, Moroni, George Washington, and Abraham Lincoln.

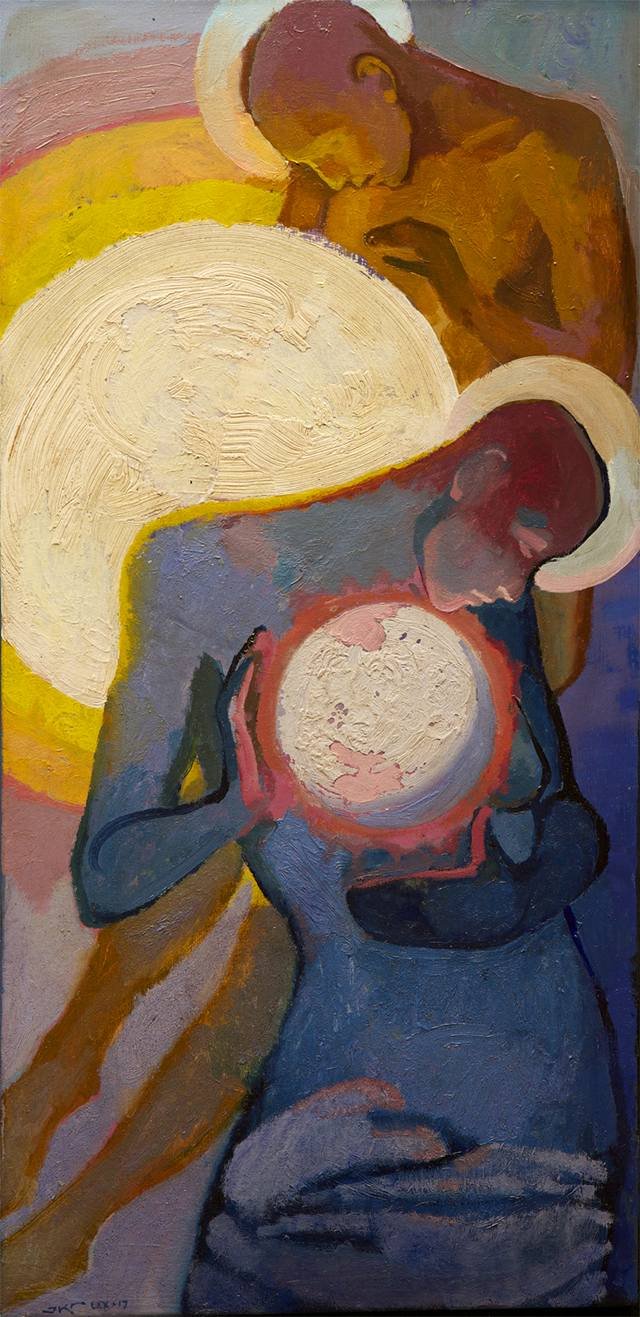

God Made Two Great Lights (2017)

Oil on panel, 20 x 10 inches

Private collection of Chris Stoddard

“And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night . . .”

- Genesis 1:16

The brightest lights in this painting come not from the halos of the divine figures, but from the works they have created. The heavenly parents’ glory seem almost an echo of their handiwork, a reflection of light in the same way the moon’s light reflects the sun. The two figures work in partnership, standing as creative equals in their movement in the cosmos. Their touch of the earth and moon looks gentle, almost delicate, as Heavenly Father’s body carefully cradles the earth and Heavenly Mother vigilantly holds the moon between her hands and chin.

This piece was part of a series entitled “After Our Likeness” Richards completed which displayed the first three chapters of Genesis, including the Creation, the temptation of Adam and Eve, and the Fall. Richards’ work, which focuses on Judeo-Christian themes, often reimagines scriptural stories in creative new perspectives.

Rocio Vasquez-Cisneros (Mexican-American, born 1998)

Hecho Por Mamá (2021)

Fabric, embroidery thread, and yarn, 35 x 24 x 24 inches

Collection of the artist

As Vasquez-Cisneros made the “beings” of this piece, she pondered the generational trauma passed down through her own family and particularly how her female ancestors struggled in the past. As the daughter of a single immigrant mother, Vasquez-Cisneros was particularly aware of the burdens that fall disproportionately on women and also how they fight to improve the lives of future generations. In her own family, women have relied on the sacred feminine to survive abuse, poverty, racism, and immigration. Acknowledging the inheritance of power that comes from that lineage helps in the healing of grief from the past.

Vasquez-Cisneros sewed the beings together with her mother, Adrianna Segura, who originally taught her to sew, and they talked about family and childhood stories as they worked. In this way, they took part in an important ritual: handiwork and textile art have been essential elements of female cultures around the world. The tradition of exchanging information while creating and working solidified relationships and produced valuable goods.

The rainbow stitching in the largest figure is reminiscent of papel picado, the perforated colorful paper banners used in Mexico to celebrate Día de los Muertos. Papel picado are very thin and wave in the breeze, representing the beauty of the fragility of life. The stitches circle around the place where a womb might be, giving honor to the generations of women who labored to bring life into the world and asking the viewer what role Heavenly Mother plays in that work.

Sarah Winegar (American, born 1993)

She ushers me into mortality, she is the keeper of the veil (2021)

Reduction woodcut print, 32 x 26 inches

Collection of the artist

Inspired by the idea that birth is a saving ordinance critical to eternal progression, Sarah Winegar wanted to portray the spiritual role a mother in Heaven might perform in pulling people through the veil into mortality. She decided to make the figure huge, a massive being to act as the divine power to give humans life as they go through her expansive space. Her face, as well as the faces of her children, are somber, aware of the struggles and trials they will face in their earthly lives. The artist wished to convey a feeling of gravity at what mortality will bring while also knowing that knowledge and growth are essential. In this depiction, while the celestial being worries about her children while ushering them into the temporal world, she would not choose another way because she knows the purpose and import of the experiences they will gain.

Melissa Tshikamba (Canadian, born 1994)

Breath of Life (2021)

Ink, watercolor, and gold leaf on paper, 12 x 10 inches

Private collection

“And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.”

- Genesis 2:7

Breath of Life reimagines the creation of the world in a way that is perhaps different from traditionally conceived. The artist takes the scripture literally, with Heavenly Mother blowing vitality into the miniature lush scene of life nestled in her hand. This piece emphasizes her role as an organizer of the universe, one whose power is intrinsic to life on earth. Tshikamba wrote of this artwork, “To me, this piece represents Mother Nature’s divine energy. God breathes seeds of light into the world.”

In this painting, the golden halo of divinity is echoed in the gold earring, a reminder of how the sacred is both universally omniscient and personally known to an individual. Tshikamba explains, “I often depict gold or circles in my artwork, which to me are symbolic of divinity, royalty, and nature.” Like some other images in this exhibition, the figure is enormous, able to hold trees and other figures in her palm. While this does not conform to the LDS belief in God having a glorified physical body, it invokes a divine presence that is more powerful and magnificent than mortality can comprehend.

Allen TenBusschen (American, born 1984)

Celestial Bodies (2015)

Oil on panel, 36 x 24 inches

Collection of McArthur Krishna

When Allen TenBusschen pondered the doctrine of Heavenly Mother, he said he “couldn’t imagine it any other way,” as this teaching had always been obvious to him. Raised by a single mother, TenBusschen’s childhood was deeply influenced by the hard-working, determined women in his life who “did monumental things with one hand tied behind their backs.”

This piece was part of TenBusschen’s desire to artistically engage with the spiritual nature of bodies without objectifying people. TenBusschen found the LDS teaching of the eternal nature of bodies compelling and his interest in the intersection of the physical and spiritual drew him to complete this portrait of his friend, Ashley. Ashley was the daughter of a mail-order bride who didn’t find out the history of her parents’ relationship until her father’s wake, an experience which drew her into a long journey of renarrating her relationship with her parents. Celestial Bodies is meant to convey the complex relationships each of us have with our earthly parents as well as with our heavenly parents. While the main figure is not intended to portray a divine being, for the artist she represents the characteristics of God: kindness, compassion, and whole-hearted love.

Amber Whitworth (American, born 1994)

What Other Power Could It Be? (2020)

Oil and prismacolor on masonite, 5 x 8 inches

Private collection of Miriam Packard-Hermansen

In the April 2014 session of LDS General Conference—the semi-annual global gathering of the LDS Church—Elder Dallin H. Oaks spoke of the roles and responsibilities of priesthood authority. Ordination to the priesthood, or “the power of God delegated to man” as Church President Joseph F. Smith defined it, is limited to men within the LDS Church. However, Elder Oaks’ surprised many listeners with the following statement:

“We are not accustomed to speaking of women having the authority of the priesthood in their Church callings, but what other authority can it be? When a woman—young or old—is set apart to preach the gospel as a full-time missionary, she is given priesthood authority to perform a priesthood function. The same is true when a woman is set apart to function as an officer or teacher in a Church organization under the direction of one who holds the keys of the priesthood. Whoever functions in an office or calling received from one who holds priesthood keys exercises priesthood authority in performing her or his assigned duties.”

With the title of her small piece, Whitworth invokes Oaks’ statement and makes her own theological connection to Heavenly Mother and priesthood power. Like many other artists in this exhibit, Whitworth places her figure in the context of cosmology, making a feminine Presence a creative force in the universe. Viewers are left to contemplate the source of her celestial power.

Ben Crowder (American, born 1983)

Their Work and Their Glory (2020)

Digital media, dimensions variable

Collection of the artist

Software engineer Ben Crowder creates minimalist religious art from the most basic geometric shapes: circles, triangles, and rectangles. He aims to represent a concept with as few lines and shapes as possible, paring back until one essential but complex idea is portrayed. By not introducing anything unnecessary to the artwork, he invites the viewer to explore a specific, clearly defined, distinct space. Reticent to portray divinity in a singular way, Crowder has completed a series of images of Heavenly Mother and Heavenly Father composed of a few lines and angles.

In this piece, two golden triangles fit together perfectly to form a parallelogram, each triangle forming its own perfect and complete shape while also contributing to a cosmic, unified form. The incomplete arc of the world bends beneath them and the viewer’s eye is drawn to the space between the shapes. We are meant to contemplate not only the perfect collaboration between the heavenly parents, but also their relationship with their earthly children.

The title Their Work and Their Work Glory references the well-known LDS scripture in the Book of Moses: “For behold, this is my work and my glory—to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.” This verse, taken from a moment in which Moses spoke with God face to face, is an important revelation about the creation of the world and the relationship God has with humanity. By altering the language to deliberately encompass Heavenly Mother, the artist expands this beloved verse to include her in the work of the universe.

Acknowledgments

The Sacred Feminine in LDS Art and Theology was organized by Margaret Olsen Hemming and made possible by the support of generous donors to the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. Graphic design for the exhibition was done by Cameron King. A special thanks to Glen Nelson, Emily Doxford, and Chase Westfall for their expertise with special projects.

Many faithful scholars and artists have helped in the restoration of the doctrine of Heavenly Mother in recent years, including McArthur Krishna, Bethany Brady Spalding, Rachel Hunt Steenblik, David Paulsen, Martin Pulido, Carol Lynn Pearson, Dayna Patterson, Tyler Chadwick, and the group Seeking Heavenly Mother. Their work laid the foundation for this artwork to be broadly accepted.

Attempting an exhibit on a sacred topic of this magnitude is formidable. Conversations with Richard and Claudia Bushman, Glen Nelson, Vinna Chintaram, Kwani Povi Winder, Kimberlee Staking, Steven Olsen, Abby Parcell, and Val and Alice Hemming were invaluable in shaping a narrative and working within the constraints of the show.

There are dozens of extraordinary pieces of artwork exploring the concept of Heavenly Mother which I wanted to include but could not. I hope this small sample of the diversity of work available inspires viewers to seek out more art and also imagine what role the sacred feminine might play in their own lives. Imagining her in every kind of body type, age, ethnicity, and race, with different roles and responsibilities is an exciting creative work in which Latter-day Saint artists are leading the way.

- Margaret Olsen Hemming, Jan. 5, 2022

Women of Faith

Listen and hear “Women of Faith” by Michael Kosorok by clicking on the image.

Lyrics by Matthew B. Biggs and music by Michael R. Kosorok (completed in 2021). Composed for voice plus descant and piano.

Recording credits:

Voices: Jessica Biggs, Matthew Biggs and Pamela Kosorok

Piano: Bradley Layton

Sound engineer: Donovan Dorrance

Logistics: Jeanette Kosorok and Michael Kosorok

Art in the video is from The Divine Feminine in LDS Art & Theology Exhibition