John Held, Jr. (American, 1889-1958)

March 16 - May 31, 2022 | Center Gallery, NYC

Upon his death at the age of 69, The New York Times observed that John Held, Jr. (American, 1889-1958) had been in his heyday, “one of the country’s best known cartoonists.” The obituary continued, “Such was Mr. Held’s reputation, he recalled recently, that people sent him blank checks to make drawings for them.” He epitomized the Jazz Age with his colorful drawings of flappers and their collegiate boyfriends, and his humor was a constant presence in newspapers, advertisements, and on the covers and pages of Vanity Fair, Collier’s, Life, Judge, College Humor, Punch, Mademoiselle, Cosmopolitan, and The New Yorker magazines. His friends F. Scott Fitzgerald, Robert Sherwood, and Eugene O’Neill defined the era, and John Held, Jr. designed it.

Held was largely self-taught—his only formal art instruction was from his father and from a fellow-Utahn, Mahonri Young. He was a drawing prodigy who sold his first cartoon for publication to Life magazine at the age of 15. Held arrived in New York City in 1912 with four dollars in his pocket, and after wartime service in the Navy working covert operations in Central America, his career back in New York took off like fireworks. By the mid-1920s, Held was a syndicated cartoonist and had magazine covers and cartoons everywhere, and he created nearly innumerable illustrations for books, advertisements, and commercial products. He lived in the era of cartoonists as national heroes. In 1927, Vanity Fair named Held to its “Hall of Fame” alongside international luminaries of the decade. The Hearst newspapers paid him $250,000 a year (nearly $4,000,000 today, adjusted for inflation) for his cartoon strip, Oh! Margy, and his drawings sold for up to $5,000 each, roughly the price of a house. His fortune changed sharply with the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the ensuing Great Depression, and a loss of much of his fortune to fraud.

His fine art works of drawings, watercolors, and sculpture have rarely been displayed, with no significant exhibition in recent decades. Few people know Held’s works for theater, movies, ballet, product design, advertising, and his writing: his four collections of short stories and four novels. Ultimately, he became a casualty of the very society of excess he satirized yet mythologized, but he never lost the connection to his childhood home. In an unpublished autobiographical essay, Held wrote: “Often in a life time one looks back and reviews certain decisions with regret. Of the many decisions I have made, good and bad, there remains one important decision that I have never regretted, that of being born in Zion, Territory of Deseret.” He added, “My Mother often said, that when Brigham Young, the Great Mormon Leader, beheld the fertile valley of the Great Salt Lake, he said, ‘This is the place,’ meaning this is the place for me to be born. I always discounted this, as I have always had a feeling that Mother was prejudiced.”

John Held, Jr. is organized by Glen Nelson with the assistance of John Murphy. It is made possible by donors to the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. Graphic design for the exhibition is by Cameron King.

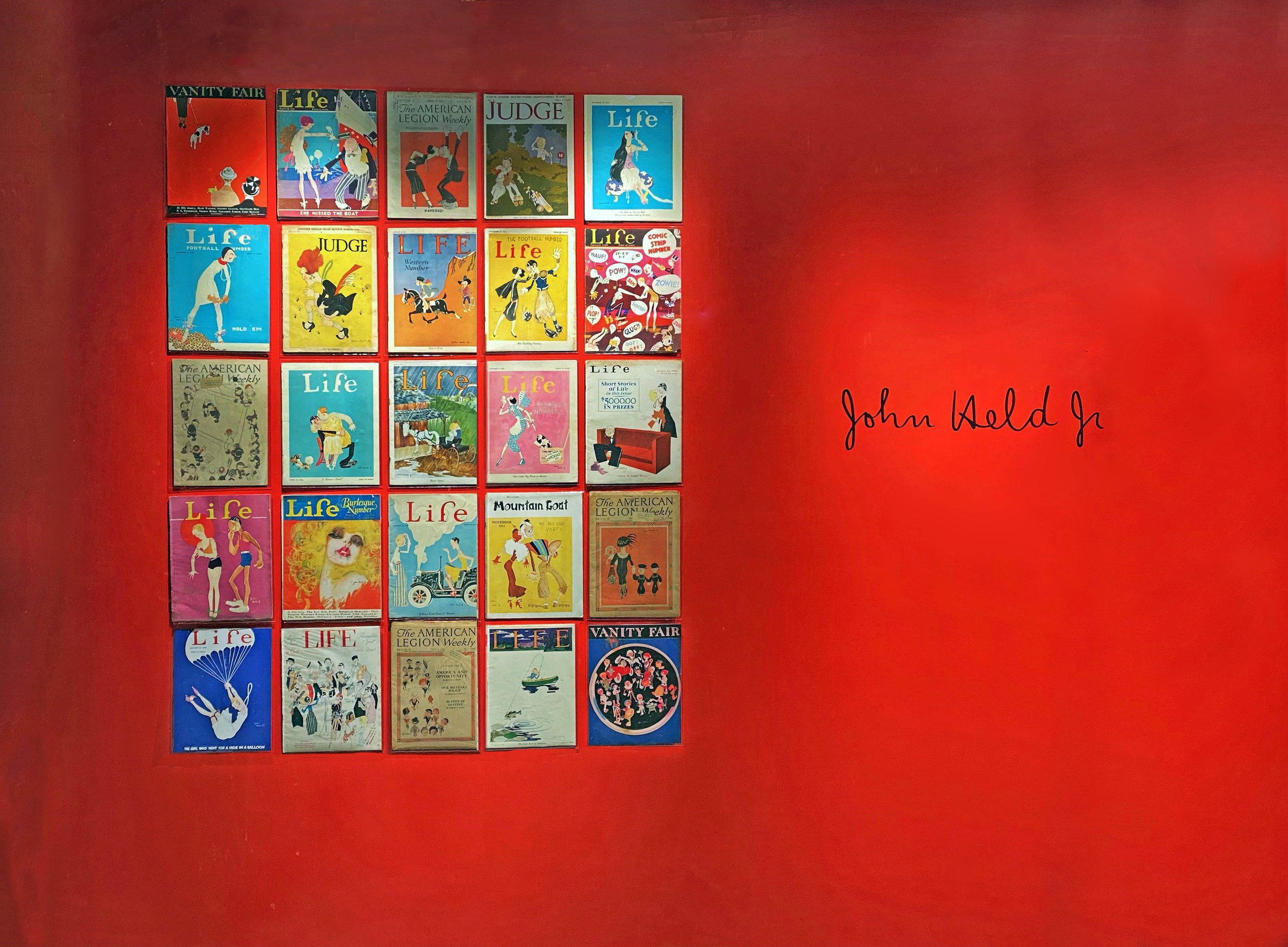

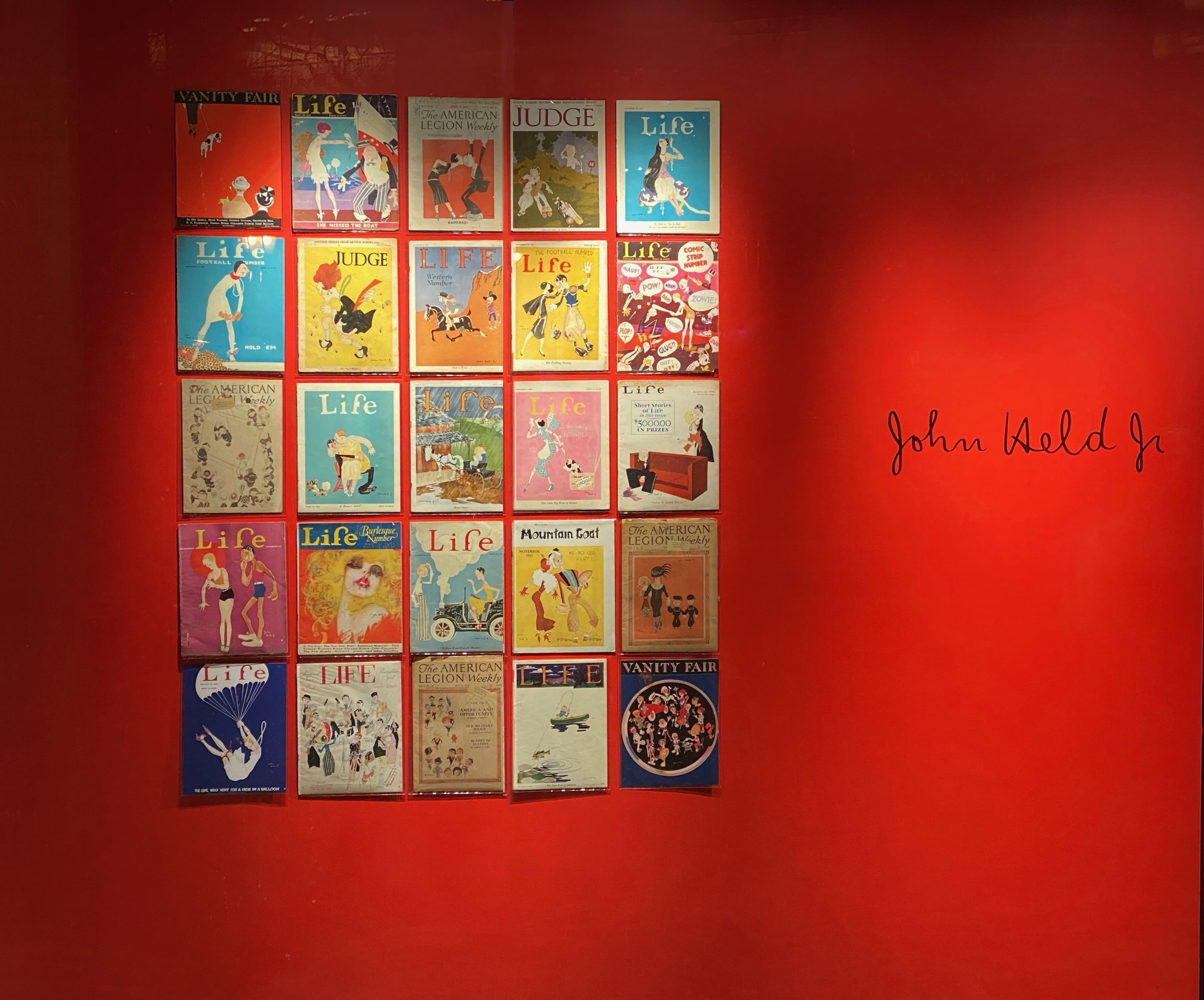

Held’s fame and fortune came from cartooning and illustration. The sample of magazine covers on display hints at the variety of images and ideas that this humorist employed, particularly in the 1920s, a time of jubilant exploration of societal norms amid a nation of shifting morals. Reviewing his influence, an author in 1967 wrote, “Fitzgerald christened it the Jazz Age, but John Held, Jr., set its style and manners. His angular and scantily clad flapper was accepted by scandalized elders as the prototype of modern youth, the symbol of our moral revolution.... So sedulously did we ape his caricatures that they lost their satiric point and came to be a documentary record of our times.”

Selected magazines with covers created by John Held, Jr. (American, 1889-1958)

Top row, left to right:

Untitled, Vanity Fair, November 1919, cover reproduction

“She Missed the Boat,” Life magazine, April 28, 1927, 32 pp.

“Kamerad!,” The American Legion Weekly, April 11, 1924, 26, pp.

“One Up, Two to Play,” Judge magazine, June 30, 1923, cover reproduction

“To Bob or Not to Bob: The girl who couldn’t make up her mind,” Life magazine, December 18, 1924, 32 pp.

Second row, left to right:

“Hold ‘Em,” Life magazine, November 19, 1925, 36, pp.

“The Bee’s Knees,” Judge magazine, May 26, 1923, 32 pp.

“East Is West,” Life magazine, January 18, 1923, 32 pp.

“Her Tackling Dummy,” Life magazine, November 13, 1924, 32 pp.

Untitled (Comic Strip Number), Life magazine, February 3, 1927, cover

Third row, left to right:

Untitled, The American Legion Weekly, May 6, 1921, 22 pp.

“A Heavy Date,” Life magazine, April 30, 1925, 36, pp.

“Horse Sense,” Life magazine, June 28, 1922, 31 pp.

“This Little Pig Went to Market,” Life magazine, October 2, 1924, 34, pp.

“Life Is Like That,” Life magazine, January 25, 1929, 32 pp.

Fourth row, left to right:

“The Girl Who Gave Him the Cold Shoulder,” Life magazine, August 26, 1926, 36 pp.

Untitled (Burlesque Number), Life magazine, May 3, 1928, 44 pp.

“A Poor Fish Out of Water,” Life magazine, October 21, 1926, 40 pp.

“We Do Our Part!,” Mountain Goat, November 1933, 20 pp.

“The Lass That Loved a Sailor,” The American Legion Weekly, May 20, 1921, 22 pp.

Fifth row, left to right:

“The Girl Who Went for a Ride in a Balloon,” Life magazine, January 14, 1926, cover reproduction

“The Talkie: ‘Now when he kisses her I’ll drop the handkerchief, and I want to hear some NOISE!’,” Life magazine, November 30, 1928, 32 pp.

Untitled, The American Legion Weekly, July 29, 2021, 22 pp.

“The Last Rise of Summer,” Life magazine, September 28, 1922, 32 pp.

Untitled, Vanity Fair, August 1920, cover reproduction

Toe Dancer on Stage, Salt Lake City (circa 1890s)

Watercolor, 6.5 x 4.25 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

This undated watercolor is notable for a few reasons. First, it was created when Held was a teenager and possibly before that. Correspondence notes that Held at a very young age began drawing anything that captured his imagination, and it mentions drawings of ballet. Held’s mother, Annie Evans, was a performer on the stage in Utah, and his father, John Held, was a noted band leader and an artist who contributed images for The Story of the Book of Mormon (1888). In New York, Held, Jr. designed for the stage. He designed sets and costumes for George Balanchine’s first ballet to an American subject, Alma Mater (1935), a story about college life, and he designed for Broadway. Later in life, he wrote a narrative treatment for a ballet he envisioned which drew from early Utah history: the miraculous 1848 story of seagulls devouring a swarm of crickets, thereby rescuing Mormon pioneers.

On the Town (Vanity Fair) (1918)

Pen and ink, 12.5 x 9 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

With only four dollars in his pocket, John Held Jr. moved from his childhood home in Salt Lake City, Utah, to New York City, in 1912, and for the next several years he worked as an illustrator for a series of advertising agencies. In 1914, with the encouragement of his childhood friend Harold Ross, who founded The New Yorker in 1925, Held added to his visual vocabulary linoleum block prints, a process he had experimented with as a young man in Salt Lake City.

Held’s early block prints were published in Vanity Fair. It was in these early block prints that Held developed, to quote the critic, Carl J. Weinhardt, “…the benignly satiric view of American life” which came to characterize so much of his future work. In this Vanity Fair cartoon, published in the last year of World War I, Held gently pokes fun at two sailors who, in search of an enjoyable night “on the town” have unwittingly purchased tickets for the opera, and have fallen asleep behind a well-dressed and sophisticated high society New York operagoer.

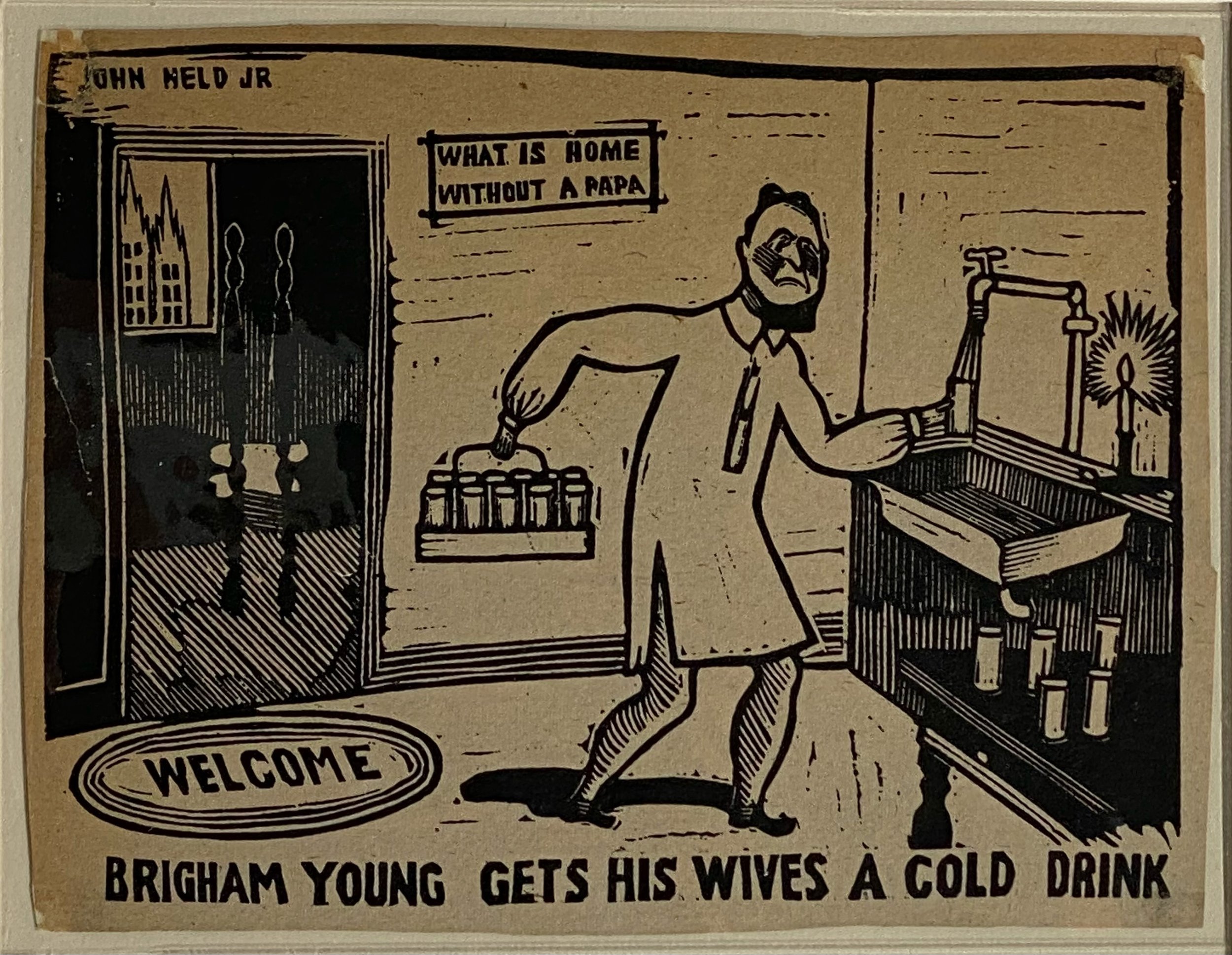

Brigham Young Gets His Wives a Cold Drink (c. 1925)

Linocut, 5 x 6.75 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

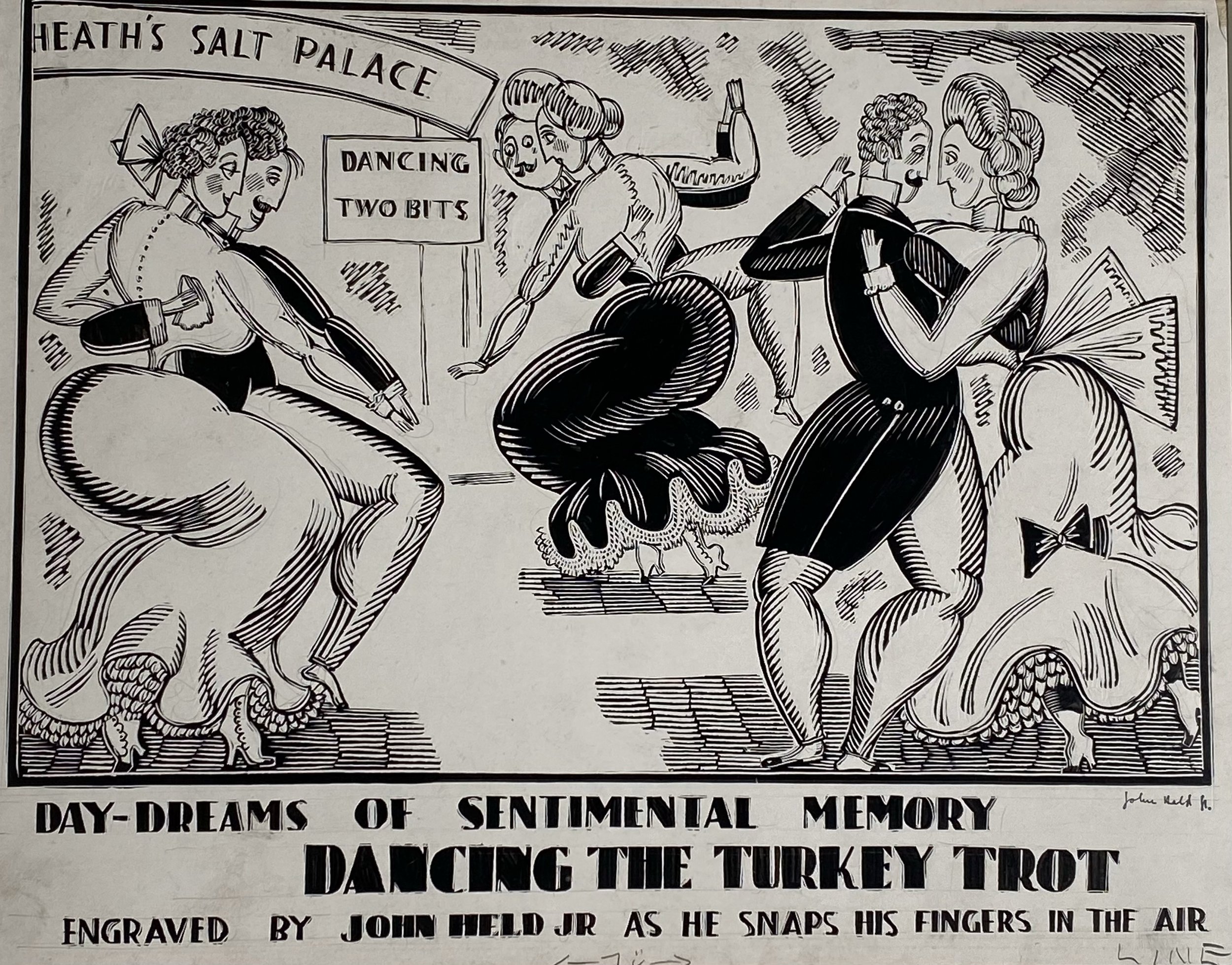

Dancing the Turkey Trot (1931)

Linocut and ink on paper, 10.25 x 14 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

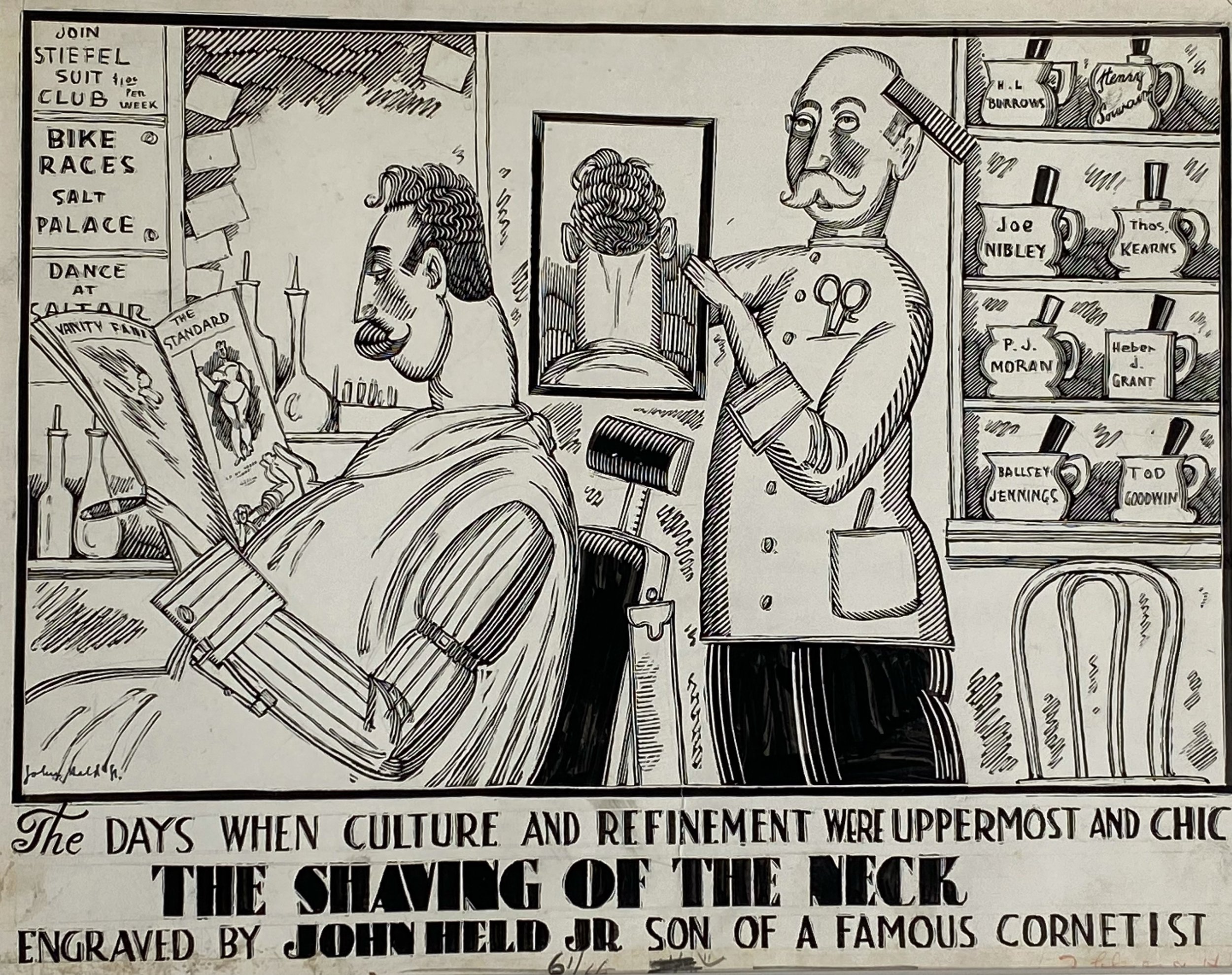

The Shaving of the Neck (undated)

Linocut and ink on paper, 10.5 x 13.75 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

Held grew up in Utah and was a fourth generation member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In his cartoons created in a faux Victorian style, he refers to LDS culture directly, its religious and civic leaders, and familiar locations in Utah. Beginning in 1925 and continuing for eight years, Held created 125 cartoons for The New Yorker magazine alone.

Untitled (1916)

Watercolor, 11.5 x 15.5 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

Lac Saint-Jean (1931)

Watercolor, 9 x 12 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

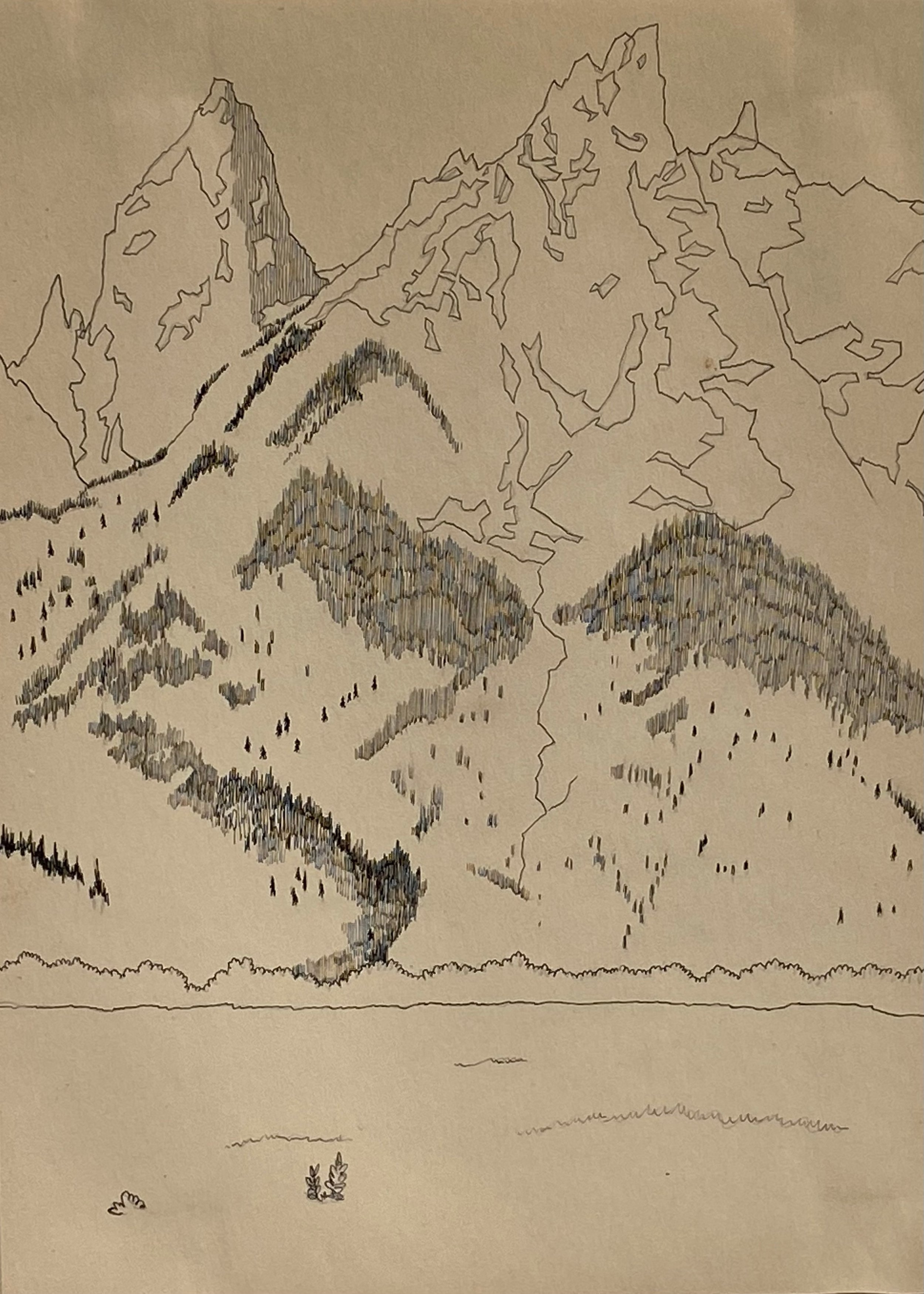

As a young boy, Held fell in love with nature. He especially enjoyed exploring the fields and mountains that surrounded his Salt Lake City home. In 1917, Held participated in an archaeological expedition to Central America sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History. It was during this trip, that Held, who also worked as an artist for American Naval Intelligence, was able to immerse himself in painting scenes of the natural world.

During the Great Depression, Held continued making landscapes including the image of the lake in south-central Quebec on display. Originally named Piekuakami by the Innu, the Indigenous people of the area, it received a French name after Jean de Quen, who was a Jesuit missionary in the area in 1647: Lac Saint-Jean.

Untitled (undated)

Pen on paper, 12 x 8.875 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

Grand Canyon (undated)

Pen on paper, 8.875 x 11.875 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

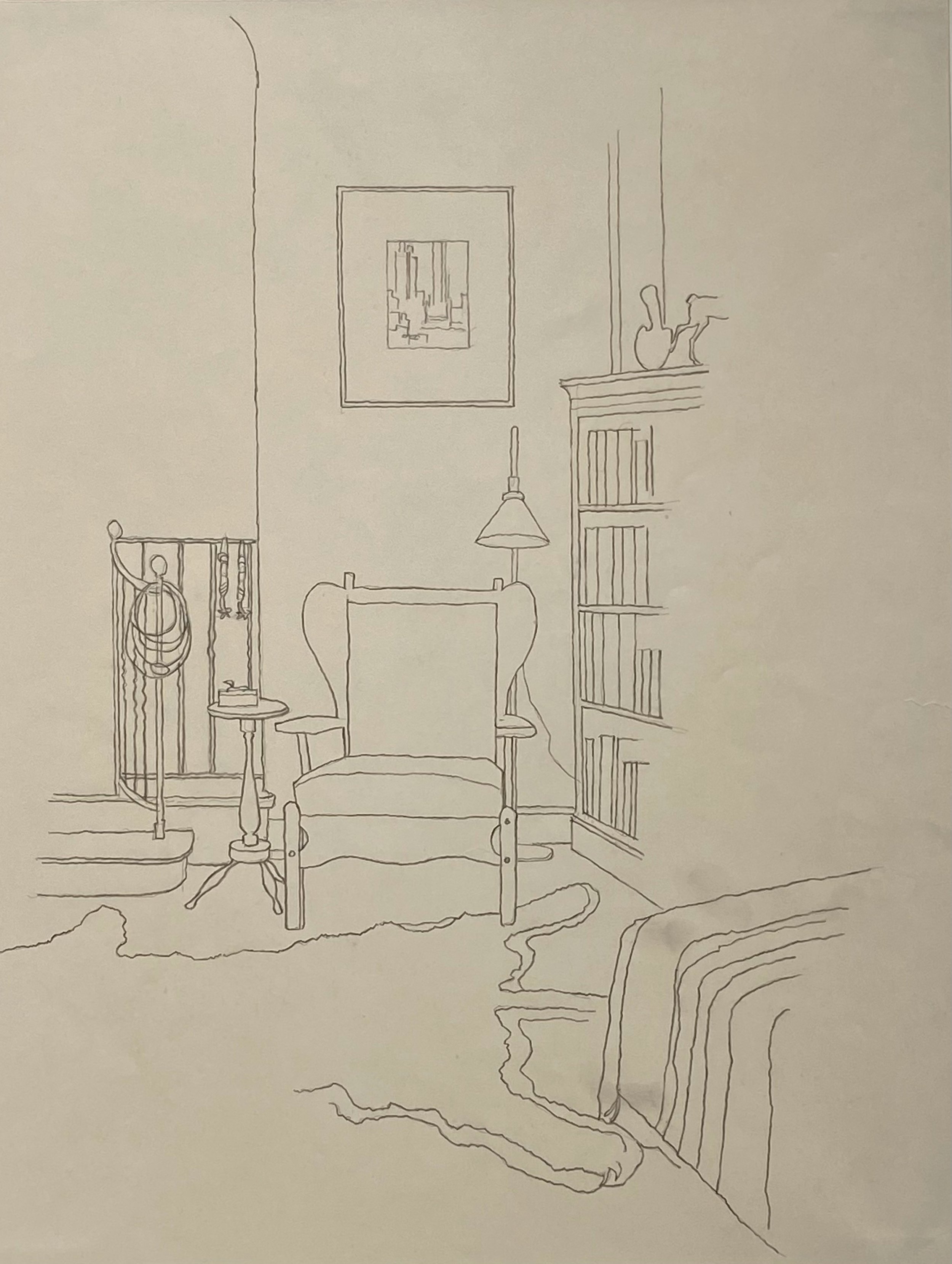

Untitled (undated)

Pen on paper, 14.25 x 10.875 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

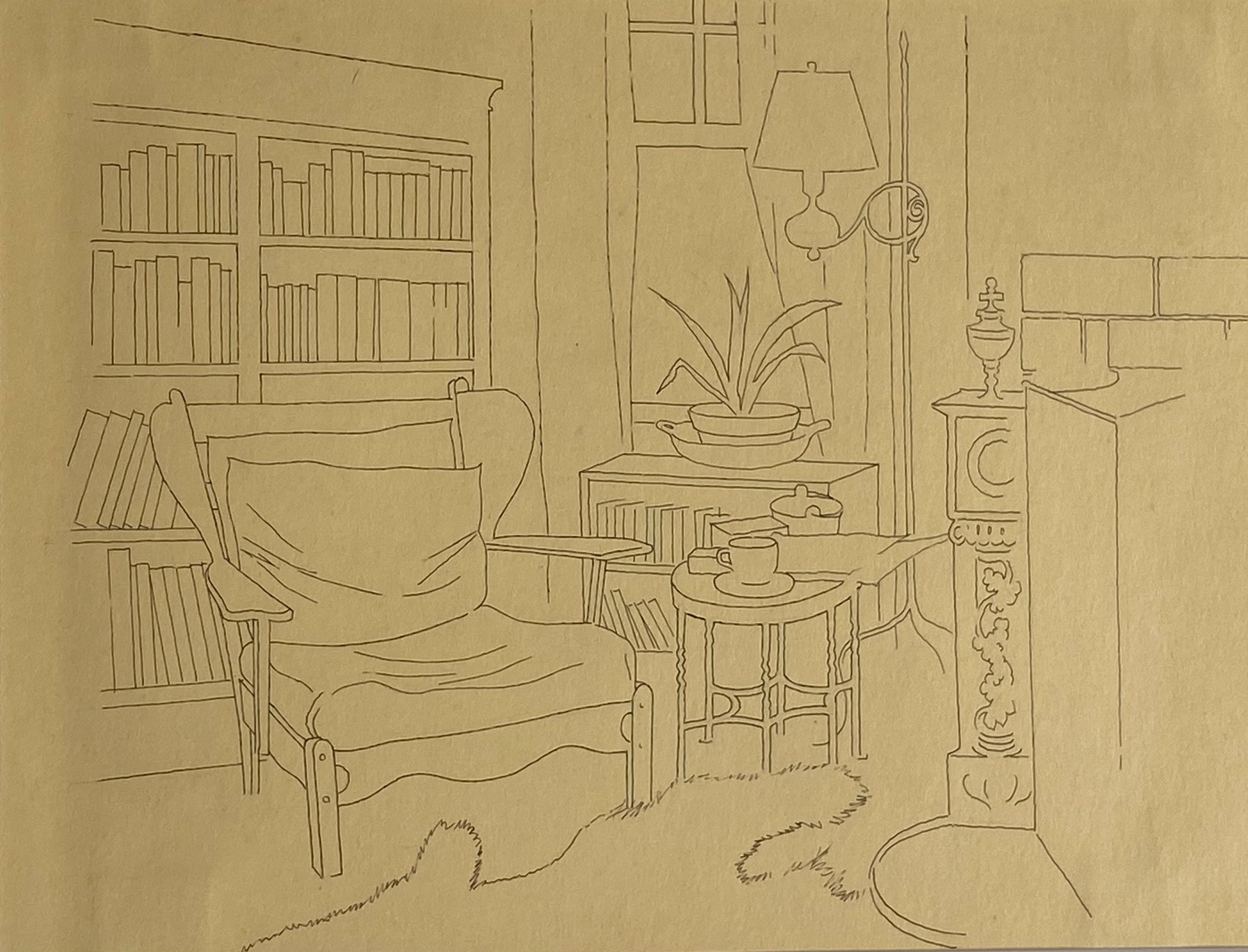

Untitled (undated)

Pen on paper, 9.875 x 13.375 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

Largely known for his color and humor, Held displayed a sophisticated and restrained sensitivity to line as well, most noticeably present in fine art ink drawings and black and white illustrations. These four drawings of landscapes and interiors—note Held’s framed artwork on display in views of his apartment—are his most modern works in that the artist has reduced their essence to a minimum of precisely placed lines without shading or traditional contouring.

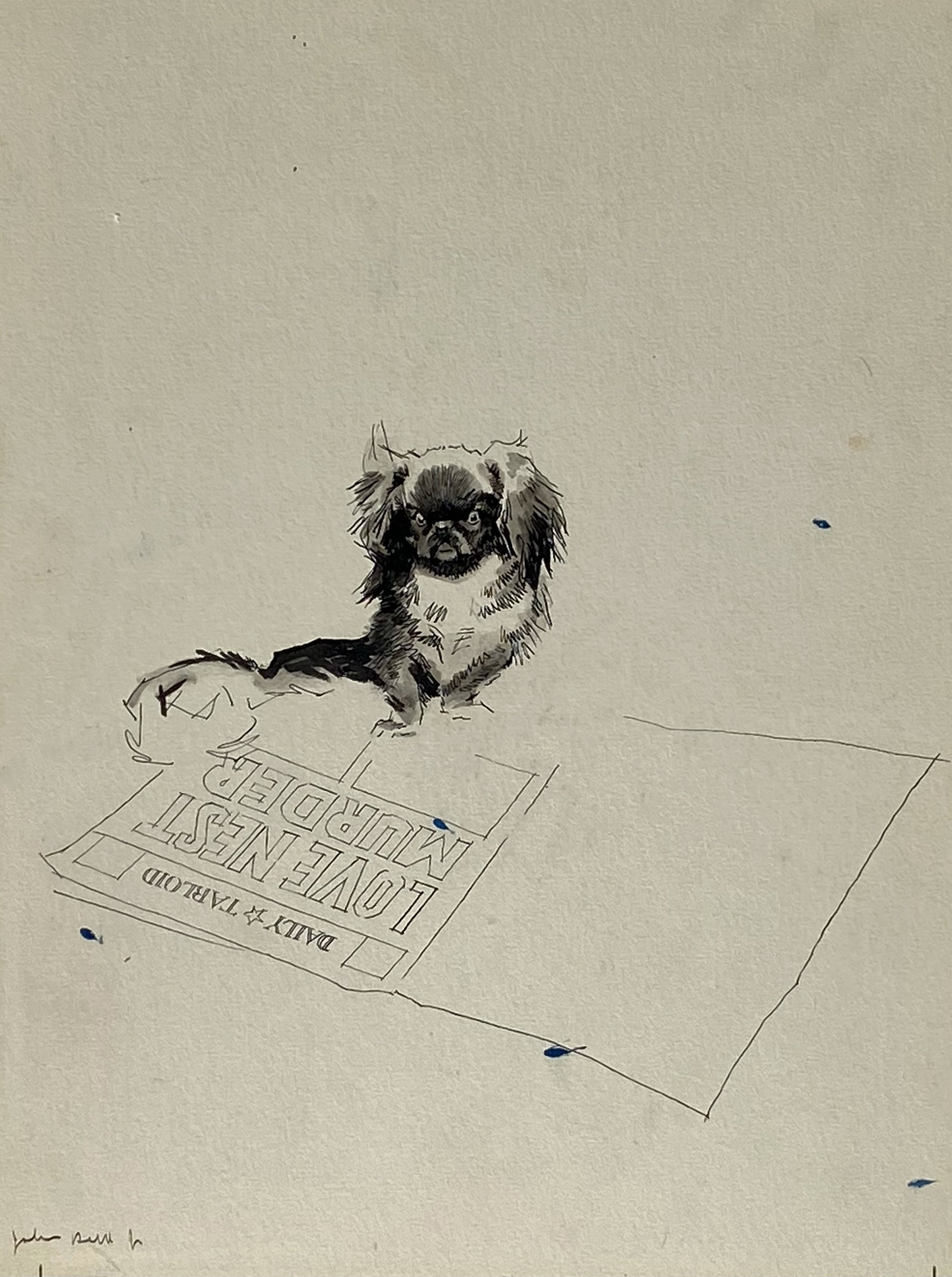

Untitled (circa 1930)

Ink on paper, 15 x 11 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

This image was used to illustrate a story, “Broadway Butterfly,” in Held’s second published collection of short stories, Dog Tales (1930). In the story, the narrator, a Pekinese lap dog, witnesses its master’s murder. Held turned to writing fiction in earnest in the 1930s, publishing four collections of short stories and four novels between 1930 and 1937: Grim Youth (stories, 1930), Dog Tales (stories, 1930), The Flesh Is Weak (stories, 1931), Women Are Necessary (novel, 1931), A Bowl of Cherries (stories, 1932), Crosstown (novel, 1933), I’m the Happiest Girl in the World (novel, 1935), The Gods Were Promiscuous (novel, 1937), followed by children’s stories: Danny Decoy (1942), The Tail of Mr. Dooley (1949), The Lamb Who Couldn’t Remember (1950), Butch & Mr. Dooley (February 1952), and Corkie (1953).

Untitled (1935)

Watercolor, 19.875 x 13.875 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

Following the end of World War I, Held returned to New York City and resumed his work with a series of New York advertising companies. During this time he also continued to paint landscapes. During the “Roaring Twenties,” however, Held spent little time drawing and painting fine art works and instead focused on the “Betty Coed” and “Joe College” drawings and illustrations that brought him fame and fortune and came to define America in the Jazz Age.

With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, the American public lost interest in the free-wheeling antics of the flappers and raccoon coat-clad college students who were the subjects of Held’s Jazz Age caricatures. Despite the decrease in demand for his drawings and several financial setbacks, the years of the Great Depression provided Held the creative space he craved to pursue his fine art passions.

“Serious art is my vice,” Held once said, and the art to which he dedicated much of his time to were landscapes and cityscapes. After 1931, Held divided his time between New York City, his Grindstone Hill Farm in Connecticut, and his new home in New Orleans. In New York, Held found solace in painting watercolors of the city and on his farm making illustrations of his beloved pets and farm animals. During the years of the Depression, Held also made several trips to the American West to visit family and friends in Utah and painted scenes of mountains, canyons, and national parks.

Untitled (undated)

Brown and verdigris plaster, 6 x 4 x 6 inches

The Private Collection of Cris and Janae Baird

During the years of the Great Depression, particularly toward the end of the decade, Held returned to an art form that he had explored as a young man in Utah, when he studied with Mahonri Young, other than his father, his only art teacher. Held never lost his interest in sculpture, and in 1938 he created a series of 18 bronzes of horses that were, in March 1939, exhibited in the Bland Gallery in New York. As stated by art critic, Howard Devree, in The American Magazine of Art, Held’s sculptures were “humorous without loss of dignity” and “alive and full of direct appeal.” Another critic, in the New York Herald Tribune, who compared Held’s work to Frederick Remingtons’s sculptures, wrote: “…his small bronzes of horses have the qualities that are only to be met with when the sculptor has an all-around knowledge of the subject, and to John Held, it may be seen that the horse is as open and understandable as a human being—or even more so.”

Soon after this New York exhibit, Held began short residency programs at Harvard and the University of Georgia, which afforded him the opportunity to not only further develop his skills as a sculptor, but also to work with students in a formal academic environment. Following America’s entry into the Second World War, Held purchased “Old Schuyler Farm” in New Jersey where he continued to paint, sculpt, and illustrate children’s books. It was an idyllic life, and it was there that he died of lung cancer in 1958.

Untitled (1935)

Watercolor, 20 x 13.875 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

Untitled (1931)

Watercolor, 15 x 11 inches

John Held, Jr., papers; L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah

Late in life, Held reflected he had wanted to come to New York to be a fine artist. Yet, he only became serious about making art other than illustration after the Great Crash, two decades after his arrival. His colorful cityscapes of Manhattan borrow from techniques used in his illustration but are elevated by spare, elegant sophistication and rich, saturated color.

Held begins his short story, “The Pigeon of Saint Patrick’s,” with this ode to Manhattan: “To fly high and look down on the great city with its deep traffic lanes, surging with thousands of motor cars and millions of people and all the tall skyscrapers pointing up at me; to see the curling smoke make dancing shadows on the roof tops; to watch the light change and make lovely colors in the dim canyons; to see the wide rivers on each side of the city with the queer-shaped boats cutting silver streaks in the water; to fly high and see all this at a glance is romantic, and don’t let anyone tell you different.”

Exhibition installation photography by Jane Feldman.