Photographs of Utah (1935-1948): Ansel Adams, Andreas Feininger, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Arthur Rothstein, John Vachon

August 13-October 10, 2021

Some 270,000 photographs were taken between 1935-1944 as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, as Rexford Tugwell, economic advisor to the president urged, “To introduce Americans to America.” Initially a program of the government’s Resettlement Administration (RA), later Farm Security Administration (FSA), and then Office of War Information (OWI), the effort to document the government’s projects for the people of the country fell to the leadership of Roy Emerson Stryker, the head of the RA’s Historical Section, who commissioned a core group of approximately a dozen photographers—from a pool of about forty—and sent them to all corners of the nation with shooting scripts to show people at work, at church, in their communities, and in their homes. The primary objective of these photographs was to justify governmental assistance programs and then to show how the country was preparing for the war. The lasting effects of the photographs became something greater than that.

Most were to become celebrated photographers, but that came later. Ansel Adams said to Stryker, “What you’ve got are not photographers. They’re a bunch of sociologists with cameras.” Nevertheless, RA-FSA-OWI photographers produced many of the iconic images of the Great Depression in America. Much less known are their images from Utah. Five of this group of photographers—plus Adams’ photographs for the Department of the Interior—captured the people and places largely unfamiliar to the rest of the country because of Utah’s geographic isolation before the Interstate highway system of the 1950s and its residents’ cultural inclination to privacy. Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (commonly known at the time as Mormons) had been victims of harassment, vandalism, even assassination in the Midwest in the 19th century. With their 1840s trek to the Rocky Mountains, they sought escape from violence. A consequence of their seclusion, however, was that many 20th century Americans knew little or nothing about them as a people.

The state of Utah itself was changing in the 1930s and ’40s. Some pioneer settlements were turning into ghost towns. Mining towns were rising and falling with economic cycles. Cities were coalescing. Copper and steel production, just in time for WWII, were becoming potent industries in the state. As Americans armed with new technologies of flash bulbs and portable cameras took to the road to explore their own nation, including an emerging network of national parks and monuments, the RA-FSA-OWI photographs of Utah—all created by outsiders looking in—beckoned them to enter, too.

Photographs of Utah (1935-1948) is organized by Glen Nelson with the assistance of Elisabeth Hunt and made possible by donors to the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. Graphic design for the exhibition is by Cameron King.

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

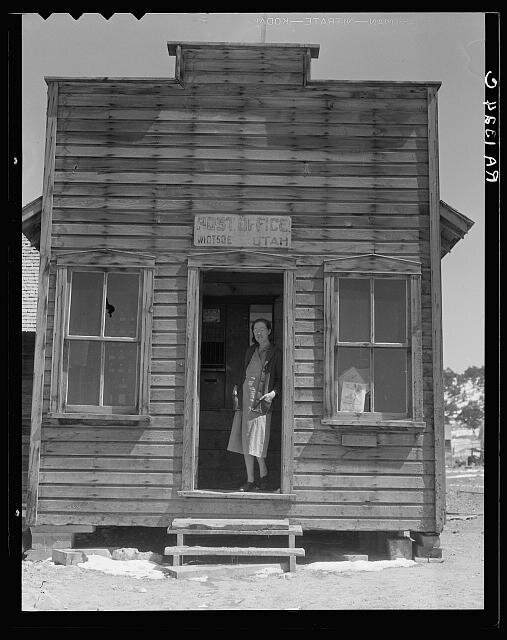

Dorothea Lange’s Utah photo assignment from the Resettlement Administration in 1936 centered on four rural towns experiencing distinct hardships during an era when the state’s unemployment rate rose above 35%. The government program needed to justify its expenditures in Utah—by 1933, more than 20% of the state’s residents had received New Deal aid, leading the nation in per capita relief. Lange traveled to the impoverished mining towns of Commerce and National, the failing community of Widtsoe—all three became ghost towns by 1950—and the isolated agricultural town of Escalante.

Her assignment to Utah was undertaken less than a month after she captured her most famous image, Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936). The public’s response to these RA images was immediate. Lange received this letter from Edwin Locke, a fellow RA photographer, in July 1936, “We are snowed under with requests for migratory labor pictures.... All this material is being grasped at eagerly by all press services, newspapers, and magazines. We are getting the greatest spread that we ever had.”

Lange’s trip to Utah resulted in emotionally persuasive photographs of resolute people on the edge. They are depicted outside their tar paper shanties and dilapidated, weathered wooden churches, stores, and homes although in some cases modern brick structures sat just outside of the camera’s view.

Came to Utah from Denmark as a Mormon convert when a boy. Now ninety-five years old. Escalante, Utah. Date created: 1936 April. Nitrate negative, 2.25 x 2.25 inches or smaller.

Post office and postmistress, view number two. Widtsoe, Utah. Date created: 1936 April. Nitrate negative, 4 x 5 inches or smaller.

Home and family of a Utah coal miner. Consumers, near Price, Utah. Date created: 1936 April. Nitrate negative, 4 x 5 inches or smaller.

The church in the center of town (Mormon). Escalante, Utah. Date create: 1936 April Nitrate negative, 4 x 5 inches or smaller

Resettlement clients to be moved from Widtsoe area to farm in another county of Utah. Date created: 1936 April. Nitrate negative, 4 x 5 inches or smaller.

Blue Blaze mine, coal town, company houses. Consumers, near Price, Utah. Date created: 1936 March. Nitrate negative, 4 x 5 inches or smaller.

Arthur Rothstein (American, 1915-1985)

The first of the photographers hired by the Farm Security Administration, at the age of 20, Arthur Rothstein noted the appeal of photographing the nation, “I was a provincial New Yorker. Not only had I been born in New York City, but I even went to college there. It was a wonderful opportunity to be able to travel around the country and see what the rest of the United States looked like...everything seemed fresh and exciting.”

Rothstein traveled to every state in the country over a period of five years, spending roughly nine months of the year on the road, but his time in Utah was limited. In March 1940, he drove through Northern Utah and shot images of the mountains, roads, and industries. Throughout his work for the FSA, Rothstein documented many miners’ homes in numerous states in the South, Midwest, and the West. In Utah, Rothstein visited a miners’ community in Bingham. These Utah images were among the last he took for the FSA. Shortly thereafter, he became a staff photographer for Look magazine, and after the war he returned to the publication as Director of Photography, until 1971. In 1977, Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, mounted a one-person exhibition of his photographs, and he later collaborated on a series of images of minority groups in the state. The Other Utahns: A Photographic Portfolio was published in 1988, three years after his death.

Wasatch Mountains. Summit County, Utah. Date created: 1940 March. Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller.

Road leading to Salt Lake Desert, Utah. Date created: 1940 March. Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller.

Miners’ homes. Bingham, Utah. Date created: 1940 March. Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller

Snow fence. Summit County, Utah. Date created: 1940 March. Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller.

ANSEL ADAMS (AMERICAN, 1902-1984)

In 1946 and 1948, Ansel Adams won Guggenheim fellowships to photograph the country’s national parks and monuments. He had been hired by the United States Department of the Interior in 1941 to shoot murals of national parks for government walls, but the war disrupted the project, which was ultimately canceled. (“Court of the Patriarchs, Zion National Park,” Utah and Rock Formation against Dark Sky, “Zion National Park, 1941” Utah on display in this exhibition are from the series for the Department of the Interior.)

Already a leading voice in American photography, and as part of the Guggenheim documentation project, Adams spent extended periods in Utah. At the time, these Utah sites included national parks: Zion and Bryce Canyon; and national monuments: Capitol Reef, Cedar Breaks, Dinosaur, Hovenweep, Natural Bridges, Rainbow Bridge, and Timpanogos Cave. Adams and his family were well acquainted with the landscape and people of the state. He sent his child to a boarding school in Mt. Pleasant, Utah, 25 miles away from Manti, the subject of his 1948 photograph, Mormon Temple, Manti, Utah. Adams selected this image of the 1888 temple in his Portfolio One: Twelve Photographic Prints. Years later, Adams invited Dorothea Lange to collaborate on a Utah photography project. In August 1953, Adams and Lange spent three weeks shooting 1,100 photographs for a Life magazine photo essay—whittled down to 34 images with texts—published in 1954, Three Mormon Towns.

Rock Formation against Dark Sky, “Zion National Park, 1941” Utah. Date created: 1941. Negative.

“Court of the Patriarchs, Zion National Park,” Utah. Date created: 1941-1942. Negative.

Mormon Temple, Manti, Utah. Date created: 1948. Gelatin silver print.

RUSSELL LEE (AMERICAN, 1903-1986)

A mainstay of the Farm Security Administration photographers, particularly in the Midwest, Russell Lee’s photographs in Utah of 1940 are unique because he was the only government photographer in the project who traversed the entire state—from Logan in the north to St. George in the south—and his photographs include interiors of people’s homes and churches. One can imagine rural Utahns suspicious of someone from Washington, D.C. who sought permission to enter into their Sabbath meetinghouses, their living rooms, pantries, and kitchens. In those days of bulky cameras with their slow film speeds that required additional lighting, how did he create the impression of a spontaneous encounter with strangers?

In 1937, Roy Stryker visited Lee and accompanied him on assignment. He wrote about the photographer’s ability to put his subjects at ease: “I didn’t get out into the field much, but one of my first trips was out to Minnesota…with Russell Lee. We were in a small town and he saw a little old lady with a little knot of hair on her head. He wanted to take her picture, but the woman said, ‘What do you want to take my picture for?’ Russell’s response was part of my education as to how a photographer thinks. He turned to her and said: ‘Lady, you’re having a hard time and a lot of people don’t think you are having such a hard time. We want to show them that you’re a human being, a nice human being, but you’re having troubles.’

‘Well, she said, ‘All right, you can take my picture, but I’ve got some friends, and I wish you would take their pictures, too. Could you come and have some lunch with me today?’ We stayed all that day and that night had supper. She invited four or five women over and Russell took pictures.”

Congregation leaving the Latter Days Saints Church at Mendon, Utah. Date created: 1940 August. Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller.

Three little Mormon girls with candy. Mendon, Utah. Date created: 1940 August. Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller.

Meeting of the priesthood in Mormon church. This meeting is held on the first Sunday of every month and includes all males fourteen years of age and older. On this morning these men do without breakfast and give the saved money to the Bishop’s fund. Mendon, Utah Date created: 1940 August Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller

Old resident of Santa Clara, Utah, with pictures of some of her forebears. Date created: 1940 October. Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller.

Before winter sets in Mormon families are well supplied with canned goods and flour. Santa Clara, Utah Date created: 1940 October Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller

Family of Mormon farmer. Santa Clara, Utah. Date created: 1940 November. Saftey negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller.

A crowd of men listening to World Series game, Saint George, Utah. Date created: 1940 September. Nitrate negative, 35 mm.

Mormon farmer shoeing a horse, Santa Clara, Utah. Date created: 1940 September. Nitrate negative, 35 mm.

Building. Santa Clara, Utah. Date created: 1940 October. Safety negative, 3.25 x 4.25 inches or smaller.

JOHN VACHON (AMERICAN, 1914-1975)

During a Spring 1942 Office of War Information expedition through North Dakota, Montana, and Idaho, John Vachon dipped briefly into Northeastern Utah and took five images in Duchesne County. Vachon joined the Farm Security Administration in 1936 as a file clerk, but after showing interest in photography, Arthur Rothstein took him out on his first assignment, and Walker Evans became an additional mentor. Vachon was not named an official photographer for the government until 1941. His FSA legacy is especially large, however, although his name is less familiar than others, for two reasons: Vachon designed how the entire archive of hundreds of thousands of images were cataloged and used; and second, Vachon was a dedicated diarist whose daily letters home chronicled both the nation and the intense difficulties of life away from family in the service of country.

Over the years, the RA-FSA-OWI changed regarding the directions Stryker gave to its photographers. The early emphasis on New Deal projects shifted to a documentation of American life, and then to a call for support for the oncoming war. What Vachon called “…the greatest documentary effort in history,” evolved, as did its values. Vachon, like Russell Lee and others, became frustrated with his inability to affect social change. Some of the government photographers had found ways to be activists, but a consequence of seeing all of America for the photographers was a newfound awareness of the problems of its people. Gradually, documentary photographers and photojournalists yearned to comment on contemporary social life, and in the 1950s, these promptings led to dissenting voices, as the Metropolitan Museum wrote, “which penetrated the country’s sunny façade to discover a newly powerful yet vulnerable nation overwhelmed by its own importance and struggling with internal strife.”

Landscape, Northeast Utah. Date created: 1942 April. Transparency: color.

ANDREAS FEININGER (AMERICAN, BORN FRANCE, 1906-1999)

The photographs of Utah that Andreas Feininger shot for the government counterbalance the body of RA-FSA images of the rural poor and their assumptions that have since been canonized as representative of the era. In fact, half of the state of Utah’s residents lived in cities during the Great Depression, and industrial processes of mining, smelting, and transporting of copper and steel were as emblematic of the state as dry farmers living in rustic pioneer homes.

In 1942, the Office of War Information sent Feininger to photograph industrial production. In June and July, he traveled to Connecticut and photographed Pratt and Whitney airplane engine and Hamilton propeller manufacturing. In October, he went to Colorado and spent part of the following three months in field stations of the U.S. Bureau of Mines and the Colorado School of Mines. Overlapping that trip, Feininger went to Utah. In November and December, he visited the Columbia Steel Company at Geneva, and Ironton, Utah, the Utah Copper Company at Bingham Canyon, its Magna and Arthur mills, the American Smelting and Refining Company at Garfield, Utah, as well as a program in Salt Lake City to train women to operate buses and taxicabs. From there, in December, he continued west to California to the New Idria Quicksilver Mining Company and finally to Washington state, where he photographed Boeing manufacturing of B-17F (Flying Fortress) heavy bombers. In all, Feininger took 639 photographs for the newly-merged FSA-OWI, which are archived in the Library of Congress—nearly all of them involving industrial production. The following year, Feininger joined Life magazine where he spent much of the rest of his prolific career.

Bingham Copper Mine, Utah. Carr Fork Canyon as seen from “G” bridge. In the background can be seen a train with waste or over-burden material on its way to the dump. Date created: 1942 November. Nitrate negative, 4 x 5 inches or smaller.

Utah Copper: Bingham Mine. Brakeman of an ore train at the open-pit mining operation of Utah Copper Company, at Bingham Canyon, Utah. Date created: 1942 November. Nitrate negative, 2.25 x 2.25 inches.

Columbia Steel Company at Ironton, Utah. Exterior view of the blast furnace. Date created: 1942 November. Nitrate negative, 2.25 x 2.25 inches.

Production. Copper. Molten copper pouring from a converter at the Garfield, Utah smelter of the American Smelting and Refining Company. This plant is producing vast quantities of the copper so vital for war purposes. Date created/published: between 1940 and 1946. Nitrate negative, 4 x 5 inches.

Columbia Steel Company at Ironton, Utah. Tapping a heat of iron in the cast house of the blast furnace. Date created: 1942 October. Nitrate negative, 2.25 x 2.25 inches or smaller.

Portrait of a woman training to operate buses and taxicabs. Date created: 1942 November. Nitrate negative, 2.25 x 2.25 inches or smaller.